I'm reading Ron Berger's Ethic of Excellence for a teaching program, and I was struck by a brief comment on page 78: “We treat our experts royally.” At my school in San Francisco, we were able to bring in journalists, CEOs, scientists, etc in the same way, and I always thought—“But I’m an expert in at least something, right?” But what is it? If these people are masters in their fields, and that qualifies them to come and talk to kids, then what am I doing here day after day? If I’m a teacher, then is that the only thing I’m qualified to teach--teaching itself?

So, Ron Berger and Larry Rosenstock were carpenters, the Shop Class as Soul Craft guy wrote about fixing bikes—how many of these progressive educators are guys who work in terms of projects naturally? If you work in terms of projects, you understand why PBL works. But then, how many teachers actually ever did their work as a series of projects, and if they didn’t, you are talking about a brain trained to think in terms of assignments.

Who in the realm of high school core subjects did professionally what they teach now? Our arts classes at MPI are phenomenal, and I suppose part of that is the creativity of the individuals who have been hired, but they are all working artists, as well—which means they inherently know how to teach their craft. But history? How many of my peers have been historians? How many working scientists or professional writers, or – mathematicians – work in high schools?

I’m thinking of the research paper, for instance—supposedly the core skill of any historical class. So, why does the experience universally suck, for students and teachers? How many teachers have actually had to do research for pay or love? Weirdly enough, I was technically on the road to becoming a professional historian, however briefly. But again, I think of the admonition that every teacher should do the project they want to assign, first. But who is going to sit around and do labs or write a research essay, or do critical analysis of novels all summer? Is that an inherent failure in what we do?

So my thinking over the past few years is to recapture what it was like in graduate school as we wrote our research papers—at least, the process, with its multiple editing sessions, peer critiquing, drafts and journaling, and presentation. The problem is how to make the research process fundamentally interesting to kids who have every reason to hate doing research.

...Especially when you have specific content that must be covered, so that the kid can’t just run off and do the first topic that intrigues him, unlike grad school, where we read dozens of books, discussed lacunae, and used that to spur us into research…

Then, I watched a TedTalk by Sugata Mitra, who discusses a series of experiments he conducted, which basically consisted of setting a computer and keyboard up in a slum in India and watching kids teach themselves how to navigate the internet and do basic computer functions, or giving a class room of kids who can’t speak English science textbooks written in English, coming back a few months later, and finding the kids have taught themselves molecular biology.

So what’s the purpose of a teacher? To be a grandmother—to offer warm praise and a “cloud” of support for the kids who have created what he calls their own “system of learning.” It’s kind of like out-Bergering Berger—the kids actually do all the teaching. Mitra wants X million dollars to replicate this throughout the worlds most impoverished neighborhoods, and I think he’s a genius.

OK—here’s the thing. It takes more time than we have in a school year to enable kids to learn their own way through a college-track education. And I taught at a school in San Fran that offered perhaps the strongest college prep experience I have ever seen. We did not do projects—we just didn’t do homework. We didn’t really do much scientific field-work or use multiple draft writing processes and peer critique feedback, and nothing much in terms of exhibitions. As a nod to student choice they could pursue an independent project, after which there would be a public presentation. We worked in isolation as teachers, though we shared dept space. There was not a strongly encouraged use of technology or a belief in interdisciplinary projects.

And yet those kids were some of the most self-motivated students I have ever seen, who were capable of dazzling work, whether it was a final product or in-class discussion. Not all were like that at all times, but enough were, in general. These kids routinely go off to the best schools in America and then they end up in the newspapers. I taught a kid who works for the Obama Administration. Others are successful artists, businesspeople, etc. Colleges love our kids, because it’s game on once they walk in the door. And they seem to think they got the best education possible, even when I extol PBL to them---they wouldn’t have had it any other way. And their families—wealthy, successful, powerful—make learning part of a home culture that makes school a seamless transition

So, is PBL/student-centered learning just a fix-it for underprivileged schools? Do we need to really think hard about the projects we assign in high school, to ensure a level of rigor to make Harvard drool at the thought of getting students like these? Is there still no real corrective to having a culture of learning in the home as well as school? Is it enough to have students select pictures that represent their thoughts about a novel and perform spoken word when other schools like that in San Fran are having students produce work worthy of Columbia University? Is PBL a rescue effort designed to reach a basic level of competence, when the upper class is still going to dominate the upper tier universities, and then go on and dominate politics and economics?

And ultimately, here’s where I struggle--I became a history teacher not because I can’t do anything else, or because history is the easiest subject to teach, but because I think it is actually the most important subject of them all. It is the only way to understand the situation we find ourselves in, whether on a personal level or a national one, and the country has been rocked by stupid decisions divorced from any real situational or historical analysis. I think it’s critically important that students understand why the country looks the way it does now. That was actually the basis for progressive education a hundred years ago—how do we as a society prepare kids to be citizens? Is it enough that Berger transformed a classroom of elementary students into activists around water pollution? I think that’s marvelous, yes. And I even had an emotional reaction to that story.

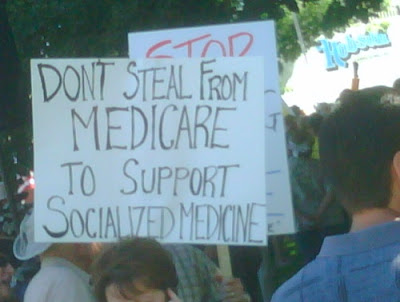

But, again my struggle—some students may go off and become physicists. Some may become engineers, some doctors, and that is an individual choice. We don’t need everyone to become one of those. But I think everyone should understand the history of our country, to understand how democracy works, to understand where our rights come from, to understand the development and evolution of our Constitution, to understand our history with race and class and gender, to understand how our economy evolved, to understand the history of our relationship to the environment—because that hits everyone on a personal level, and anyone can become an activist. That’s what history trains you for, and our democracy needs that. You can’t look at the Tea Party and not see a fundamental ignorance about our country in action, right? And if their philosophy becomes the governing one in our country, they can do horrible damage. Which means other people’s ignorance can have nasty consequences for me, no?

So it’s not enough for me that 3 kids in my class become Constitutional “experts;” I want them all to be. And yes, I know, most history teachers are not. I don't have answers--these are just concerns and questions.